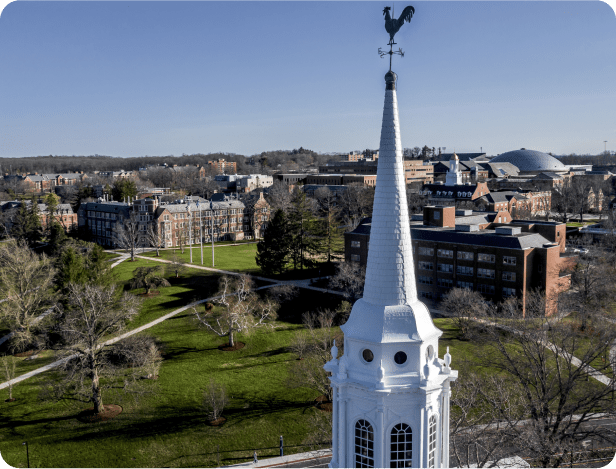

Recycling and repurposing organic waste

Organic waste makes up roughly 40% of the waste stream in the U.S. At our state-of-the-art recycling campus, we convert waste into methane, capture it, then supply it to our local community in the form of renewable energy.

What we do